Compound Time Signatures – Part 22e

Scales in Music – a Tonal System

Scales in Music – a Tonal System

Music Theory – Level 2

Compound Time Signatures – Part 22e

Welcome to Compound Time Signatures – Part 22e, the fifth part of the Time Signature mini-series within the Music Theory Section of our overall article series Scales in Music – a Tonal System.

Overview

In Time Signatures – Part 22d we reviewed the simple meter time signatures using musical extracts from classical works from three major classical composers; Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. We will now be taking a look at compound meter time signatures using additional extracts from within the classical music repertoire by two additional classical composers Igor Stravinsky and Gustav Holst. Both Parts, 22d and 22e will then provide a resource for you to review these concepts in case you need a reference source of information about the simple and compound meter time signatures.

Two example applications are provided one each for the 5/4 and 7/4 time signatures. An extract is taken from each musical work and an audio file is provided to demonstrate the ideas included in the compound time signatures.

All of the extracts used in the examples within this article are in the public domain and therefore do not need any copyright clearance.

Prerequisite Articles

To gain the greatest amount possible from this article, it is advisable to be familiar with the additional articles in the Time Signature article series; Parts 22a, 22b, 22c and 22d, as well as reviewing the Musical Note and the Note Identification articles necessary for understanding note and rest values. It would also be a good idea to review Speed in Music – Tempo which will assist you in understanding more about tempo and its influence on time signatures.

Perfect and Imperfect Time vs. Simple and Compound Time

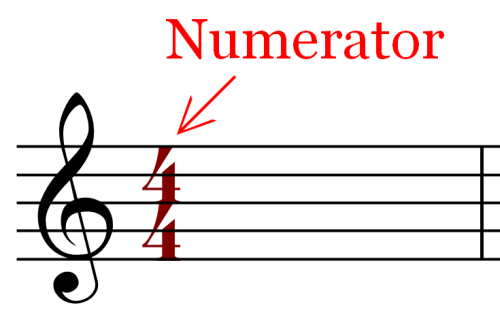

Before beginning our presentation on compound meter it is important to make some important distinctions when learning about time signatures. The time signature itself designates either perfect time or imperfect time simply by the numerator that is being used as the top number in the time signature. Also, depending upon what the numerator is divisible by, this will determine whether the time signature is in simple time or in compound time. Let’s take a closer look at each of these to learn the important distinctions between them.

Perfect Time – In perfect time the numerator must be equally divisible by 2 or 3 to be classified as a perfect time. This means that the numbers 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 16, 18, 24, 32 or 48 when placed in the numerator or top position of the time signature, all are considered as being perfect time signatures. Again, each of these numbers is divisible by either a 2 or a 3.

Imperfect Time – If the numerator is not equally divisible by a 2 or a 3 it is considered as imperfect time. Any time signature using the numbers 5, 7, 101, 11, 13, 142, 153, or 214 when placed in the numerator position of the time signature the meter is considered to be in imperfect time.

Simple Time – If the numerator is divisible only by 2 it is considered as simple time. Examples of simple time would include all of these time signatures; 2/1, 2/2, 2/8, 2/16.

Compound Time – If the numerator is divisible by 3 it is considered compound time. Examples of compound time would be 6/2, 6/4, 6/8, 15/16 or 18/32 as examples.

As you continue learning about time signatures you will discover that you can use a wide variety of time signatures within your compositions. You will also discover several more categories of Time Signatures in more advanced studies of them. For now, let’s examine our main topic compound time signatures.

Compound Time Signatures

Remember, compound time signatures are determined by the numerator or top number of the time signature symbol. For comparison purposes let us review the Simple Meter 4/4 time signature to use as a reference point in further discussions.

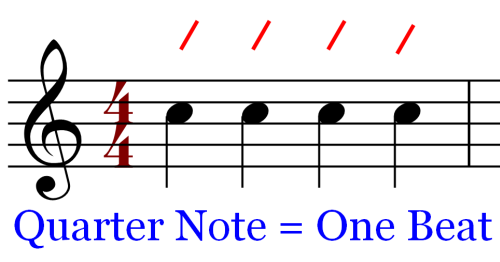

Simple Meter 4/4 – The chart below shows the simple time signature of 4/4. The numerator, the top number 4, is divisible equally by 2 therefore this is an example of simple time.

When using the 4/4 simple time signature each beat is filled using either a note or a rest or a combination of notes and/or rests which fills the required beats in the measure. The bottom number designates the note value or rest value which gets the equivalent of one beat. In the above case the lower number 4 stipulates for us to use a quarter note or quarter rest to equal or fill up one beat. The chart above reflects this idea using 4 quarter rests to fill the required number of beats in the measure.

When using the 4/4 simple time signature each beat is filled using either a note or a rest or a combination of notes and/or rests which fills the required beats in the measure. The bottom number designates the note value or rest value which gets the equivalent of one beat. In the above case the lower number 4 stipulates for us to use a quarter note or quarter rest to equal or fill up one beat. The chart above reflects this idea using 4 quarter rests to fill the required number of beats in the measure.

In 4/4 time you can also think of this time signature as 2 duples where the first set of two quarters notes is one duple and the second set is by default the second duple. Although this is not all that necessary it is the beginning of understanding more complex time signatures.

A duple is simply two notes where the first note is stressed or accented. This concept will be more thoroughly demonstrated when discussing the 5/4 compound time signature below.

Compound Meter 5/4 – Moving on to the next chart which shows the compound time signature of 5/4. The numerator 5 is not equally divisible by a 2 or a 3 however each part of the time signature includes the quantity of 2 quarter notes (a duple), filling the first two beats, and a quantity of 3 notes (a triple or a tuple) filling the last three beats. When added together they equal the required number of beats designated by the numerator in 5/4 time, 2 beats + 3 beats = 5 beats.

Each of the five beats is fully satisfied by the use of a quarter note filling one beat as designated by the denominator or lower number. Again, it is instructing you to use a quarter note or a quarter rest for each beat within the measure. The numerator 5 is the top number instructing you to play a total of five beats within the measure. All requirements are satisfied for each part of the time signature. The 5/4 compound meter is also considered to be in imperfect time because it is not equally divisible by a 2 or 3.

The 5/4 time signature is also called quintuple time or 5 beats per measure. In the chart above, the first note of the duple and the triple is generally accented as shown in blue above. Reversing the note groupings where a triple is followed by a duple is also acceptable when using the 5/4 time signature. In fact, you could group any combination of notes together as long as the total beat requirement is met. In all of these cases a person’s initial experience with this time signature is awkward and quite a different experience than the more commonly used simple time signatures.

Ccompound Meter 7/4 – The next chart shows an example of the 7/4 compound time signature in comparison to the 5/4 compound time signature just presented.

In this case the 7/4 compound time signature is using the number 7 as the numerator. This is also called septuple time or 7 beats per measure. Here again, the denominator is a 4 so a quarter note gets one beat. The number 7 is not equally divisible by 2 or 3 making this a compound time signature as opposed to a simple time signature. Just as in the case of the 5/4 meter, the 7/4 is also an imperfect time signature.

The first set of three notes or the triple is part one, if you will, of the number of beats in the measure and the quadruple is the second set of notes fulfilling the total required number of beats per measure, in this case 7, (3 + 4 = 7). The first note of each set of notes is accented as shown in blue.

The note groupings in 7/4 time can be reversed as well, by creating a quadruple followed by a triple for example. This practice is perfectly acceptable as well. In fact, you could group any combination of notes together as long as the total beat requirement is met. Here again, a persons initial introduction to this time signature also feels quite awkward and it takes a bit of time and practice to fully appreciate the 7/4 time signature.

Classical Music Applications

In consideration of the two examples used to review compound time signatures let us now take a look at extracts from classical music demonstrating the use of the 5/4 and the 7/4 compound time signatures.

Application – The Planets, Gustav Holst

Our first example comes from Gustav Holst from his beautiful work The Planets, Op.32. In particular is the first part of this work titled Mars: the Bringer of Wars where Holst opens the piece using the 5/4 time signature. Holst uses the full symphony in this work.

In the full score, one learns that the first two measures opens with the rhythm carried in the strings, harp and by the timpani. From measure three Holst brings in the woodwinds, specifically the oboes and bassoons as well as the horns. The clarinets are added to broaden and to “fill up” the overall sound. This is an amazing musical work which you will want to study as you become more familiar with orchestration and advanced composition.

Holst – 5-4 Time Signature – col legno – Clip

To keep this explanation as simple as possible we have reproduced a three measure extract of the 1st Violins to demonstrate the 5/4 time signature. This musical extract makes explaining the 5/4 time signature very easy to do. Also, you will notice that it is performed using a technique called col legno in this case by the violin.

In the original score the repeat sign is not included. I have used it here to demonstrate the 5/4 time signature.

The example is not the easiest for this level of instruction with the introduction of the triplet and using the col legno technique however it does provide clear direction for the use of alternative time signatures.

Extract Analysis

Measures 1, 2 and 3 – Holst started each of these measures with one triplet, a three (eighth) note combination with the same duration or value as one quarter note. The next two quarter notes complete the triple filling the first three of the five beats required in the measure. The fourth beat is comprised of two eighth notes and it is followed by a quarter note to complete the duple as well as completing the required number of beats (5) for this measure as designated by the 5/4 time signature. Measure 1, 2 and 3 are identical.

The Triplet – Referring back to the triplet – The color of the triplet is dark brown to make it easier to see. The number 3 is placed above the measure to designate that a triplet is being used. Sometimes a horizontal bracket is also placed when designating the use of a triplet.

A triplet is made up of three notes. In our example, we used 3 eighth notes. The triplet’s duration in total is equal to the normal time span of one quarter note. Normally 3 eighth notes would equal 1-1/2 quarter notes.

“What happens in a triplet is twofold;

First, each note of the triplet is of equal duration as the other notes within the triplet unless otherwise designated. In essence they are steeling time from each other.

Second, the total duration of the triplet is equal to the next larger note value. A triplet comprised of 3 sixteenth notes is equal in duration to one eighth note. A triple of 3 quarter notes is equivalent in duration to one half note.”

In our example we used the eighth note in the triplet therefore the total duration of the triplet (made up of 3 eighth notes) is equal to the total duration of one quarter note. Consequently, the triplet fills only one beat within the measure under the time signature of 5/4 as used in our example above for instance.

Application – The Firebird, Igor Stravinsky

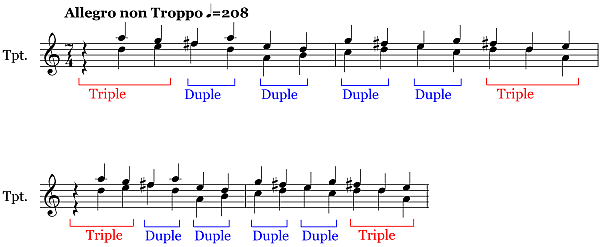

For the 7/4 compound meter example we are using an extract from Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird. It comes near the end of the composition, at measure 203. Stravinsky used the 7/4 time signature altering the note sets within the measures while staying in the 7/4 time signature, thus creating a very unique sound and effect for this work.

The main melodic theme is produced within the brass section of the symphony and primarily presented in the trumpets and the tuba. The melody is carried using full strings and the woodwinds, specifically the oboes and the clarinets.

To keep this more simplified, we are using a four measure extract representing the 2-voice Trumpet part in 7/4 time signature from the Firebird composition. I have chosen to present only the trumpets at this point in time. I do not wish to lose any of my audience by presenting the entire symphonic section using all instruments written by Stravinsky.

For more advanced students, please refer to the full score for The Firebird as this magnificent work is an excellent study for future composers and an excellent refresher course for those currently composing music. If you have not studied The Firebird score, I would highly recommend getting a copy of the full study score of this musical masterpiece. It will certainly expand your knowledge and capabilities for improving your advanced compositional skills.

7-4 Clip From The Firebird – Stravinsky

In this example, Stravinsky mixed up where the duples and triples fall within the measures. These note sets were arranged where measures 1 and 3, are the same and measures 2 and 4 are identical as well. Let’s examine them closely. The time signature is designated as 7/4 allowing for seven beats where a quarter note or quarter rest gets one beat.

Measure 1 – In measure number one begins with a full quarter rest followed by two quarter notes completing the first triple of the first measure. The remaining beat requirements are fulfilled by adding two sets of duplets completing the total of seven beats. The mathematics looks like this;

(1 + 1 + 1) + [(1 + 1) + (1 + 1)] = 7 beats

Measures 2 – For measure number two, we see that Stravinsky reversed the order of triples and duples while still fulfilling the seven beats for the measure. For this measure the mathematics looks like this;

[(1 + 1) + (1 + 1)] + (1 + 1 + 1) = 7 beats

Measure 3 – Reverts back to the same arrangement as measure number one. The mathematics looks like this;

(1 + 1 + 1) + [(1 + 1) + (1 + 1)] = 7 beats

Measure 4 – Stravinsky returned to the same arrangement in measure 2 using it again here in measure 4. For this measure the mathematics looks like this;

[(1 + 1) + (1 + 1)] + (1 + 1 + 1) = 7 beats

In all cases as used in these extracts each beat requirement has been met using the 7/4 time signature designation. The audio clips should provide additional support for you to hear the 7/4 time signature fairly easily in both extracts. For those just starting out I would suggest playing the audio clips several time to get the feel of compound meter. The 5/4 and the 7/4 time signatures are sometimes not easily recognized by new composers or new performers, so please take your time and review them often until you come to appreciate them.

Compound Time Signatures Recap

We began this lesson by describing the differences between perfect and imperfect time. Perfect time was defined by being able to divide the numerator equally by a 2 or a 3. Imperfect time was defined by not being able to equally divide the numerator by a 2 or a 3.

We continued to make further distinctions by defining both simple time and compound time where simple time is determined by being able to equally divide the numerator by a 2 or a 3 and compound time is defined by the opposite where the numerator cannot be equally divided by a 2 or by a 3.

We continued by presenting the 5/4 and the 7/4 compound time signatures as well as providing a comparison to the simple meter time signature of 4/4.

Our example for the 5/4 compound time signature was an extract taken from Gustav Holst and his superb composition, The Planets. An introduction to the triplet was also presented and we will be discussed triplets in more detail in a later article. The Planets is highly recommended for further study.

An extract from The Firebird by Igor Stravinsky was used to demonstrate the 7/4 compound time signature. His use of the duples and triples provided an interesting use of them as well as offering evidence of the flexibility of their use. The Firebird is also recommended for further study.

Conclusion

The two articles, Part 22d and Part 22e, in this series on Time Signatures, are useful in a study of simple and compound meter. The notation examples, audio files and the descriptions should help you to thoroughly understand the differences between them. Collectively the time signatures as described within the whole series, provides a complete review of the concepts involved as well as their usage in music composition.

Up Next

We have two more articles to complete our current study of time signatures. The next article is titled Changing Time Signatures – Part 22f. It will be followed by the final article of this series titled; The Effect of Tempo on Time Signatures – Part 22g.

Please proceed to Changing Time Signatures – Part 22f.

Reference Material

Numerators that are not divisible by a 2 or a 3 are considered to be imperfect time. If any of these numbers; 5 or 7 are part of the division they are classified as imperfect since the number 5 or the number 7 are not divisible by a 2 or a 3 any numbers involved in the division which are imperfect causes the time signature to also be imperfect. Here are the referenced imperfect numerators from above.

Imperfect Numerators

101 is considered to be a double quintuple (2 x 5) time signature and therefore not divisible by 2 or 3.

142 is considered to be a double septuple (2 x 7) time signature and therefore not divisible by 2 or 3.

153 is considered to be a triple quintuple (3 x 5) time signature and therefore not divisible by 2 or 3.

214 is considered to be a triple septuple (3 x 7) time and therefore not divisible by 2 or 3.

Note: All charts were produced using Sibelius 6 a product of Avid Technologies.

Compound Time Signatures